Stories of publishing English version of 'A Dream of Red Mansions'

Editor's note: "A Dream of Red Mansions" (Hongloumeng) is a classical Chinese novel written by Cao Xueqin in the 18th century. An English version of it, translated by famed translators Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang, was first published by Foreign Languages Press in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The book's editor Ye Junjian recounted some of the lesser known stories behind its publication.

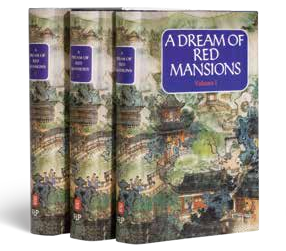

English version of"A Dream of Red Mansions," first edition (1978), translated by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang.

The English version of "A Dream of Red Mansions" is the first classical novel translated and published by Foreign Languages Press. The translation and editing work began in the early 1960s and lasted for nearly 14 years until the first volume of its English version was published in 1978. As the book's editor, I get emotional whenever I recall that journey. However, this difficult period also taught me what I needed to learn about foreign publishing, and turned a young college graduate into a competent editor.

A complex and difficult project

The translation, editing, designing, and publishing of such a masterpiece is a complex and difficult project. As a young graduate, I felt a lot of pressure being the book's editor. I had to study conscientiously with senior editors and learn from practice. The senior editors at Foreign Languages Press had accumulated rich experiences, and one of the most important working methods was to get out of the office and invite experts and scholars to help with the editing. Most of our publications followed this rule, which turns out to be very effective. This publication was no exception.

When we first started the translation work, we visited many experts and scholars in the field of Redology (academic study of the novel), including famous names like He Qifang, Wu Shichang, Zhou Ruchang, Yu Pingbo, Deng Shaoji, Li Xifan, A Ying, and Qi Gong. They offered invaluable assistance on selecting the book's editions as the base script, copy editing our translations, annotations, and illustrations and binding design.

In addition to getting the experts' opinions and feedback, we also invited a number of them to participate in our work. We invited renowned translators Yang Xianyi and his wife Gladys Yang to do the translation, and Wu Shichang, a researcher at the Literature Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, to verify the translations of the first 80 chapters. We also invited Qi Gong from Beijing Normal University to help edit our annotations, Li Xifan to write for the preface, and Dai Dunbang to create the illustrations. Their contributions had ensured the success of our work.

Selection of editions

The selection of editions was the first problem we encountered in our project, one that is common to the publication and reprinting of ancient classics. Over the past two centuries, the book has had many versions, with both hand-copied editions and block-printed editions. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, the People's Literature Publishing House published a 120-chapter edition of "A Dream of Red Mansions" in 1957, based on the block-printed edition published by Cuiwen Books in 1792. This edition is popular among general readers in China. Another one is a hand-copied 80-chapter edition published by Youzheng Books in 1911, which is considered to be closer to Cao Xueqin's original work. In 1958, the People's Literature Publishing House published this edition revised by Yu Pingbo.

Which edition should we choose to be the original script for our translation? We consulted many experts and eventually decided on the 120-chapter edition. This is because we thought that the Chinese ancient classic should be introduced overseas as a complete story, and that the most widely read and studied version was also based on the 120-chapter edition. For the first 80 chapters, we chose the photocopied version of the 80-chapter" The Story of the Stone With the Preface by Qi Liaosheng," and the last 40 chapters from the 120-chapter edition, both published by the People's Literature Publishing House. The latter is a relatively authoritative version of the book popular back then with the last 40 chapters written by Gao E.

With hindsight, it might not have been the best choice. If there could be a revised English version in the future, I hope that I can make further efforts to find a more ideal version.

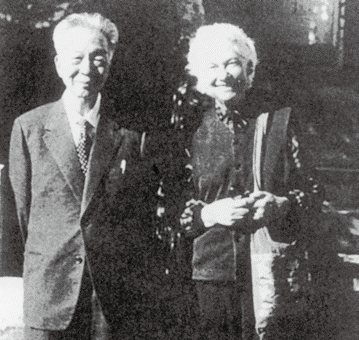

Yang Xianyi (L) and Gladys Yang, English translators of "A Dream of Red Mansions"

Translation, copy editing and annotation

Yang Xianyi was a famous translator working for the Chinese Literature magazine, and his wife, Gladys Yang, was a British translator. They were the first to translate "A Dream of Red Mansions" into English and introduce it to the outside world. As early as the 1950s, the couple worked together to translate some chapters of the book into English and published them in Chinese Literature, and won praise from foreign readers for their accurate and fluent translations. When we considered the translators of the book's English version, they were naturally the best candidates. It turns out the 120-chapter version translated by the couple is indeed the world's only complete and most authoritative English edition of "A Dream of Red Mansions."

The first volume of the English version was published in 1978, and the other two volumes were published in 1980. It has been reprinted three times since then, and its second edition was published in 1995. Another edition combining the three volumes was also published. In June 1992, the Spanish edition, translated from English, was published in four volumes.

Double checking the book's English version was an extremely arduous task, which required someone to have a solid foundation in Chinese literature as well as a good command of the English language.

Based on the recommendation of Yang Xianyi, we requested Wu Shichang, a researcher at the Literature Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, to verify the translated work. Wu used to teach Chinese literature at Oxford University and was also a Redology expert, and his involvement was another boost to our translation work.

The book involves many Manchu customs and complicated names of objects. The translator needed to find the accurate equivalent in English to make the English version as faithful as possible to the original work. Therefore, we invited Qi Gong, a professor at Beijing Normal University, to be our consultant. He wrote annotations for the 120-chapter version of "A Dream of Red Mansions" published by the People's Literature Publishing House, and was a descendant of the Manchu royal family. Because of his familiarity with the customs and various items described in the book, his participation in our project made the translation more accurate and appropriate. Qi was also a famous calligrapher, and he wrote the Chinese title on the cover of the book's English version.

We made Qi's acquaintance during the later years of the Cultural Revolution. I can remember we almost got lost on the way to visiting him at his residence for the first time. He lived at a relative's home at the time -- a shabby bungalow in Beijing's Xizhimen area. Two or three bookcases, a desk, and a single bed filled his small room. The desk was full of books and paper rolls. The small window made the room very dim. We can feel deeply the hardship the Cultural Revolution had brought to him. Yet, Qi remained a generous and optimistic person with a broad and hearty smile. He welcomed us warmly and met our requests with no hesitation. For us, he was a friend in need and a friend indeed.

Illustrations from Dai Dunbang

It also took us a lot of time and effort to decide what kind of illustrations to use in the book. The 120-chapter version of "A Dream of Red Mansions" published by the People's Literature Publishing House uses color illustrations drawn by Cheng Shifa. Can we use them?

Also at that time, some people suggested the use of single-line illustrations in ancient copies, on the grounds that it would be more consistent with such an ancient classic. But how could we find them? Could we use them if we found them? With these questions in mind, Wu Shousong, who was in charge of the book's designing, and I went to the library of Peking University and the Beijing Library, which was originally located in the Imperial College (Guozijian). We spent several days flipping through those ancient copies and ditched the idea of using those illustrations due to the fact that they are poorly printed and mostly damaged with the passage of time.

According to the protocol of the art and literature editorial department at our publishing house, the illustrations in most foreign publications were newly created, instead of using existing illustrations from their Chinese versions. Who would create the illustrations for this book? After listening to the recommendations from art experts, Wu and I went to Shanghai to request Dai Dunbang from China Welfare Institute to create the illustrations. In Shanghai, a staff member of the Shanghai Federation of Literary and Art Circles asked us why we did not invite Liu Danzhai, who was more celebrated than Dai, to do the job. I did not answer him directly, but thought popularity was a relative thing, and someone not yet famous could still become famous in the future. After Dai completed his 36 illustrations for the English version of "A Dream of the Red Mansions," his popularity increased and became a celebrated artist with a unique style.

Dai's illustrations for the book were later displayed in overseas exhibitions multiple times and were compiled into a book and published in China. The art designer Wu was also awarded at a national book binding exhibition for his design of the book.

Looking back at this journey, my deepest feeling is that a competent editor needs not only solid professional knowledge, but also strong organizational abilities. More importantly, the project gave me a golden opportunity to learn from hands-on work. These experiences have laid a solid foundation for my future career in editing, and gave me the strength to take on other important tasks such as the foreign publications of "Mao Zedong Poems" and "Dictionary of Chinese Names."

The article is originally written in Chinese and included in the book "50 Years of Memoir at China International Communications Group" published by the New Star Press in 1999. The article is translated by Guo Yiming.